|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| BESSLER, Johann

|

| Triumphans Perpetuum Mobile Orffyreanum

|

| Kassel 1719

|

| First edition.

|

| 4to, half vellum and boards.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

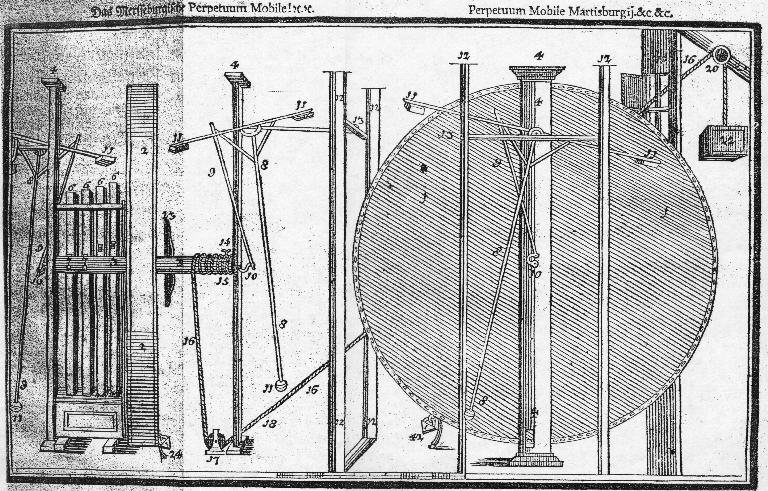

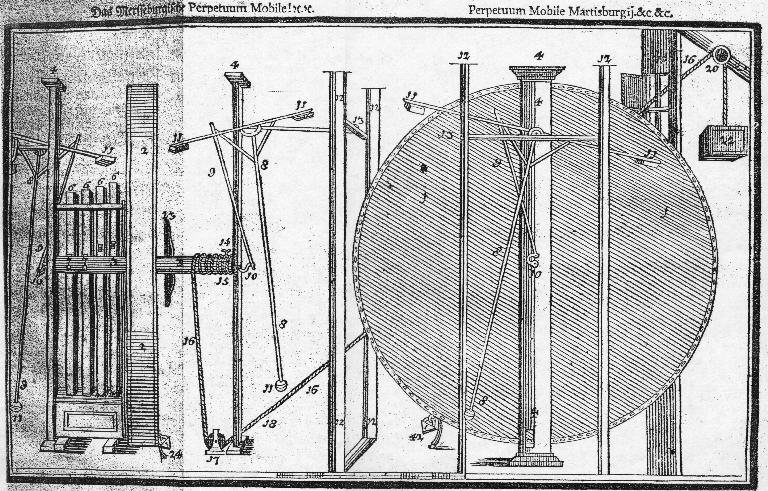

Identifying himself by the cabbalistic pseudonym Orffyreus (which is a cyclic substitution based on the letters of his own name, shifted by thirteen letters and then latinized), Johann Bessler built and demonstrated history's most famous and controversial "perpetual motion" machines. His devices were large rotating drums, which suggests to the casual observer that they most likely used some variation on the overbalanced wheel concept, but their continuing notoriety stems from the remarkable persistance of their motion - running for weeks without apparent fatigue under the scrutiny of respected outside observers. Because Bessler was secretive, combative, and very clever, there is today no clear explanation of how his wheels worked. Even his own report on the devices (Triumphans Perpetuum Mobile Orffyreanum Kassel 1719) is too cryptic and incomplete to answer the important questions.

|

|

|

|

Bessler owes much of his fame to the particular timing of his efforts, which were expended from about 1710 until 1720. By the beginning of the 18th century, scientists had gained real celebrity among the educated classes, having demonstrated some remarkable effects and insights while cultivating a reputation for careful critical thinking, which gave them a degree of credibility that often exceeded their actual expertise. Some among them nevertheless recognized that, although they had resolved many well-known mysteries of science, they had not yet fully mastered Nature's rule book, and their natural skepticism should be tempered with a little humility. One of them - Professor s'Gravesende of Leiden, whom history has recognized as one of the great 18th century authorities on mechanics - was open to the possibility of perpetual motion, and went to Kassel at the invitation of Bessler's patron to see the machine. His subsequent letter to Isaac Newton (published in 1721) probably had more effect than any other public notice in securing Bessler's place in history:

|

|

|

|

"It is now more than seven years since I conceived I discovered the paralogism of those demonstrations [that perpetual motion is impossible], in that, though true in themselves, they were not applicable to all possible machines; and have ever since remained perfectly persuaded, it might be demonstrated that a perpetual motion involved no contradiction ... The inventor [Orfyrreus] has a turn for mechanics, but is far from being a profound mathematician, and yet his machine hath something in it prodigiously astonishing, even tho' it should be an imposition ... You see, Sir, I have not had any absolute demonstration, that the principle of motion which is certainly within the wheel, is really a principle of perpetual motion; but at the same time it cannot be denied me that I have received very good reasons to think so, which is a strong presumption in favour of the inventor."(Henry Dircks, Perpetuum Mobile, Amsterdam: B.M. Israel, 1968, p 40.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

The timing was ideal - science appeared to be rapidly driving the magicians and charlatans from the temple, but even at the highest level there was still room for the discussion of implausible phenomena, although it required a truly impressive demonstration to overcome the prevailing skepticism. Had Bessler lived seventy five years earlier, he would have been lost in a sea of mechanicians pretending to have invented perpetual motion; had he lived seventy five years later, he would have been ignored completely.

| |

| |

Bessler was most likely not a charlatan (in the sense of someone deliberately practicing fraud), but genuinely believed he had made a perpetual motion device. Within the scientific paradigm of the period, the subtleties that differentiate a very efficient machine from an impossible ideal would not necessarily have been apparent, even to an expert. His secrecy would also have been unsurprising in Europe at that time, where the occult traditions of the craft guilds lived on. Bessler's story is summarized by Rupert Gould in Oddities, A Book of Unexplained Facts (London 1928).

| |

| |

The figure is a view of the wheel at Castle Wissenstein in Kassel, taken from this pamphlet.

|

|

|

|